Firmware at Bare metal

Published:

In this tutorial, we are going to look at writing firmware for an embedded hardware device. This tutorial is solely focused on simulations. However, it can be synthesized to work on FPGAs.

We are using the following setups,

- picoRV processor as the hardware.

- riscv-gnu-toolchain to compile the firmware.

- Iverilog for simulation.

Introduction

Firmware is usually written with c and assembly. Additionally, a program needs to have a memory map so that it can map the firmware to the correct places to start the boot process properly. The following diagram shows how things get connected in the process of producing the final binary.

stateDiagram-v2

direction LR

State1 : Source files written in c (*.c)

State2 : Source files written in assembly (*.s)

State3 : Object file (*.o)

State4 : Linker script (.lds)

State5 : elf file

State6 : Binary or Hex file

State1 --> State3

State2 --> State3

State3 --> State5

State4 --> State5

State5 --> State6

Now, let’s get in to each of the component briefly. We will be looking at each component seperatly. In this tutorial, we will look at the default firmware given in the picoRV.

sample c program to run on our setup

#include "firmware.h"

void hello(void)

{

print_str("hello world\n");

}

Do we need to have a main { } function here? Actually where to start in a c code should be acknowledged by the programmer to the processor. This should be implemented in assembly language.

sample assembly code

reset_vec:

// no more than 16 bytes here !

picorv32_waitirq_insn(zero)

picorv32_maskirq_insn(zero, zero)

j start

/#ifdef ENABLE_HELLO

/* set stack pointer */

lui sp,(128*1024)>>12

/* call hello C code */

jal ra,hello

#endif

Although we have multiple objects like different c programs multiple assembly programs, we need to compile them into one single program. For that, we need to have a linker script.

sample memory map

MEMORY {

/* the memory in the testbench is 128k in size;

* set LENGTH=96k and leave at least 32k for stack */

mem : ORIGIN = 0x00000000, LENGTH = 0x00018000

}

SECTIONS {

.memory : {

. = 0x000000;

start*(.text);

*(.text);

*(*);

end = .;

. = ALIGN(4);

} > mem

}

Simple Experiment

Now let’s start with the real deal by identifying each step

clone the full version of the above code from GitHub. Contents related to this tutorial are available in the folder tutorial1 of the repository

git clone https://github.com/Archfx/rv32firmware

cd rv32firmware/tutorial1

Setting up the toolchain

Instead of setting up the toolchain in your local machine you can use the following docker container and mount the firmware directory to it

docker pull archfx/rvutils

docker run -t -p 6080:6080 -v "${PWD}/:/rv32firmware" -w /rv32firmware --name rvutils archfx/rvutils

This will get you to a docker container with the toolchain. Now, all we got to do is compile the firmware. Once you are in the docker container navigate to the tutorial1/fw folder. This contains all the firmware related files for our processor.

docker exec -it rvutils /bin/bash

cd rv32firmware/tutorial1/fw

Compiling the Firmware

producing the output file

- compiling the c files to machine code

riscv32-unknown-elf-gcc *.c -c -mabi=ilp32 -march=rv32ic -Os --std=c99 -ffreestanding -nostdlib - Compiling the assembly files to machine code

riscv32-unknown-elf-gcc start.S -c -mabi=ilp32 -march=rv32ic -o start.o - Using the linker to link with the machine code to a single program

riscv32-unknown-elf-gcc -Os -mabi=ilp32 -march=rv32imc -ffreestanding -nostdlib -o firmware.elf -Wl,--build-id=none,-Bstatic,-T,sections.lds,-Map,firmware.map,--strip-debug start.o firmware.o -lgcc - Generate the binary from .elf

riscv32-unknown-elf-objcopy firmware.elf -O binary firmware.binFor simulations, we need the hex file

- Generate the hex file

riscv32-unknown-elf-objcopy -O verilog firmware.elf firmware.hex

Simulating the Firmware in picoRV

Here comes the fun part. Now we have the compiled firmware which can be run on the actual hardware. Instead, we are going to simulate the firmware on the hardware implementation as a simulation. For this, we are using Iverilog simulator. Iverilog is an open-source compiled simulator, therefore this process involves two simple steps. First, we need to compile the hardware design combined with the firmware. Then run the compiled simulation.

- Let’s connect the firmware to the hardware implementation. For that either we can modify the test bench or pass the firmware as a parameter for the compiled simulator (+firmware parameter in step 3).

cd hw nano icebreaker_tb.vand find the following lines on the test bench. Modify the firmware file location to the correct firmware that you just compiled.

reg [1023:0] firmware_file; initial begin if (!$value$plusargs("firmware=%s", firmware_file)) firmware_file = "../firmware.hex"; $readmemh(firmware_file, mem.memory); end - Now let’s simulate. First, we compile the design

iverilog -s testbench -o ice.vvp icebreaker_tb.v icebreaker.v ice40up5k_spram.v spimemio.v simpleuart.v picosoc.v picorv32.v spiflash.v -DNO_ICE40_DEFAULT_ASSIGNMENTS "`yosys-config --datdir/ice40/cells_sim.v`" - Finally, run the simulation

vvp -N ice.vvp ../fw/firmware.hex +firmware=../fw/firmware.hex

This will produce the below output in the terminal

VCD info: dumpfile testbench.vcd opened for output.

0000000

+50000 cycles

+50000 cycles

+50000 cycles

+50000 cycles

+50000 cycles

+50000 cycles

icebreaker_tb.v:37: $finish called at 3000000000 (1ps)

You can observe the internal signal patterns by looking at the testbench.trace and testbench.vcd files.

Let’s observe whether our program is executed by processor

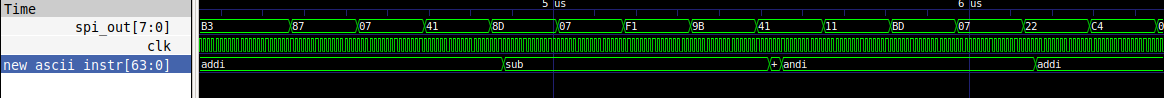

Indeed, the processor executed the instructions from the SPI flash, which we added by compiling the firmware. The above VCD dump is showing the spi_out values corresponding to the below line in the firmware.hex and relevant instructions executed by the processor.

@00100000

...

B3 87 07 41 8D 07 F1 9B 41 11 BD 07 22 C4 06 C6

...

In the next post let us look at how to write firmware in a detailed manner.